The above photo shows the author standing between two miners who were also

As an Amazon affiliate, I earn a small commision, at no additional cost to you, whenever a qualifying purchase is made.

For years, before I took up metal detecting, I made my living

Sniping is a simple, age-old, mining method used to home in on and recover concentrations of placer gold from natural caches, accessible with simple hand tools—on or near bedrock.

Partly because

Once the suspected cache of gold is located and worked, the sniper quickly moves on to work the next likely spot. A lone sniper commonly powers through multiple caches in a day.

Sometimes, when large sections of bedrock are exposed, caches may be close together and keep a sniper busy in one place for hours, or a day or more. Most times caches are farther apart, requiring the sniper to hike from one to the next.

While

Readers will come away with a fundamental understanding of the geological processes leading to the deposition and concentration of placer gold in streambeds. They will also become familiarized with the basic tools and techniques needed to target and recover placer gold from streams. In addition, they will learn what gold caches are, how to spot them, and how a skilled sniper works them to extract gold.

Placer Gold

Snipers focus almost exclusively on placer gold. Placer gold is gold that has congregated into what’s called a secondary deposit after it has eroded from its original bedrock source. Placers occur in both wet and dry environments.

Placer gold is being harvested every day from countless auriferous (gold-bearing) stream beds in the United States. And placer gold is found throughout the world in watercourses that, for learning purposes, are virtually identical to the one we are about to explore.

However, before we can proceed, effectively, it’s crucial to understand the meaning of a most important term—Bedrock. As every gold prospector knows, bedrock is truly foundational to the mining game.

Gold veins form in bedrock. Bedrock is the solid rock that underlies our entire planet’s surface. In many cases bedrock is exposed as a surface we can see and walk on.

Bare bedrock can often be encountered in mountain ranges, especially at the upper elevations. Most bedrock though, such as the bedrock underlying the valleys we live in and underpinning the gold-bearing streams we mine, is covered by a largely unconsolidated layer of broken rock and soil known by prospectors as overburden.

Now, let’s get down to business! Let’s visit and study a typical gold-bearing creek streaming through a narrow canyon, over 2,000 feet below its ridgetop. The stream’s channel drops in elevation, on average, 30 feet per mile—ideal for the deposition of gold along its craggy course.

Along the creek’s path, there has been sediment (overburden) deposited on its banks and in its bed in the form of clay, silt, sand, and gravel, ranging in size from microscopic particles to, in some cases, boulders dwarfing automobiles.

The overburden, deposited over eons, is composed of materials eroded from the canyon’s walls, mixed with gravel introduced upstream by merging channels during times of flood and from chunks torn out of the stream’s own bed during the canyon-cutting process.

In some sections, the overburden is deep and covers the bedrock in the channel like a thick blanket. While in others, almost always in the steeper and narrower sections where the stream’s flow rate and ability to transport materials has increased, the overburden is thin to non-existent, leaving patches of bedrock exposed both in the water and along the banks—sniper’s delight!

Typical Mother Lode Country gold-bearing stream with exposed bedrock along its banks

Over eons, the erosion process deepens a stream’s channel and digs a canyon by breaking up and removing countless tons of material. Gold, if present, is released from bedrock veins and seeks its natural place to settle in the stream.

However, in California’s Mother Lode Country, the preponderance of the gold in present day creeks and rivers came from the breaching and plundering of rich, dead and buried, ancient Tertiary River channels by present-day streams.

The sand and gravel in the stream’s bed and along its banks from canyon wall to canyon wall may seem to be permanent landmarks. However, in reality, the entirety of it is on a journey towards the sea—a very slow journey by our standards perhaps, but a journey, nevertheless.

What’s going on, simply put, is a massive canyon-cutting operation where over a vast period of time natural forces have cut the canyon to its present depth. If left unmolested, the process will continue until the streambed is excavated down to base level.

*Base level is the elevation at which a stream empties into the sea or an inland body of standing water such as a lake and loses its ability to erode.

Until a stream reaches base level it will continue to perform as a giant conveyor belt, methodically eroding its bed and transporting its load (materials carried in suspension). Heavier overburden, from pebbles to massive boulders, are upswept and forced along its channel during violent spurts of flooding.

Typical Mother Lode Country canyon

Typical Mother Lode Country canyon

Gold, discounting platinum, is the heaviest constituent of consequence to snipers found in an auriferous stream’s lode of silt, sand, and gravel.

(Plantinum in river placers have rarely been found in the United States in concentrations worth mining.)

Specific gravity is the ratio of the density of a given volume of material to that of an equal volume of water at the same temperature.

The specific gravity of water is one (1.0). Any substance that has a specific gravity greater than one, will sink in water.

The specific gravity of common river gravel falls between 2.4 and 2.7. Quartz comes in at 2.65.

Gold is heavy! Pure gold has a specific gravity of 19.3, which equates to 19.3 times as heavy as an equal volume of water.

Consider that a pint (28.9 cubic inches) of water weighs 1.04 lbs (avoirdupois), therefore an equal volume (28.9 cubic inches) of gold weighs 19.3 times 1.04 lbs—which equals 20.072 lbs avdp or 24.39 pounds troy.

Precious metals, including gold, are weighed and traded globally using the troy weight system. In the United States we use the avoirdupois pound system of weight measurement for most commodities. Click here to convert between troy and avoirdupois weight.

It should be easy to understand, why gold, because of its high density, tends to settle on or near bedrock as it separates and descends from the lighter gravels that are stirred up and transported during events of periodic flooding. It’s common for the precious metal to escape the current, descend to bedrock, and lodge firmly in cracks and crevices as well as beneath and behind boulders and other anomalies and obstructions in the streambed. There it becomes safe from eviction, except in the most cataclysmic of events.

It has been well-established that gold, as a general rule, will be found in its highest concentrations on or near bedrock.

Curly Dan, also known as CD, is a gold sniper. He’s camping and

The stream he’s working is only 30 or 40 feet wide in places, expanding to as much as two hundred in others. It is remote and over 2,000 feet below the canyon’s ridgetop. The fact that there are no trails in the vicinity makes trekking up and down the steep canyon walls difficult. It can be risky.

Before we learn more about CD and watch him snipe for gold, let’s touch on the topographical features and flora and fauna native to his

Among the trees sprouting from the stream banks and canyon walls are cedar, conifer, cottonwood, madrone, maple, oak, and willow. Deer come daily and drink skittishly from the creek; watersnakes lurk in pools to ambush trout. Rattlers and other snakes stalk prey on rocky sand bars and canyon walls.

Grey squirrels scamper about in the treetops while their cousins, the scruffy browns, scramble over rocks on the canyon floor. Blue Jays screech and scold from treetops. Giant, German brown trout patrol the deep pools beneath frothy waterfalls. Darting about, shark-like, they gobble insects, larvae, and other morsels flushing through the current from upstream.

California Newt

From December to May, California Newts, members of the Salamandridae family, migrate down the canyon sides by the thousands from their underground homes to gather in the stream’s cold, clear pools. There they mate and deposit slimy clusters of eggs (incubation chambers for the next generation).

In the spring, water lilies grow broad, green leaves shaped like elephant ears and drape them bare inches above the waters of placid ponds and gentle eddies. Brush along the stream banks becomes thick—impassable in places.

Ladybug Jamboree

Ladybugs arrive to cluster and mate in huge, dynamic masses and purposefully lay their microscopic eggs among plants heavily infested with aphid colonies (meat for their progeny).

Poison oak becomes more potent, no-see-ums (tiny gnat-like flies) and blood-sucking mosquitoes hatch and swarm by the millions.

CD first arrived on the creek in early spring after the heavy winter rains subsided. He located his camp at the confluence of a minor tributary, where he pitched his modest, camouflage tent on a gravel bar, behind a dense thicket of bushes up against the canyon wall—effectively cloaking his shelter from casual view.

He was

If the creek pays well, he may work out of his new camp for a week or longer before moving it again, if not—if it pays poorly or not at all, he’ll move downstream or relocate to a different drainage altogether. Such is the life of a professional gold sniper.

One early morning after breakfast, CD hustled into his gear and sped off to work. Hiking up the center of the creek, he glided over wet, slippery rocks and boulders, as carefree as if he were jaunting along a city sidewalk on a Sunday afternoon. He was wearing a worn, tattered wetsuit.

Neoprene patches covered the places were his suit had worn through. Over his kness and elbows, were homemade knee and elbow pads, meant to cushion his wetsuit from wear when crawling over jagged streambeds in search of gold. From hard use, his pads had ragged holes worn in them; bare skin poked through in spots.

His diving mask was pushed up above his eyes to rest on his forehead, so as not to restrict his vision as he hiked up the creek. In his hands were his

Beneath his wetsuit was a peanut butter sandwich, cigarette tobacco, rolling papers, and a butane lighter packaged into waterproof, zip-lock bags and pressed against his bare chest. Higher up under his suit was his gold bottle, pressing against him and causing his wetsuit to bulge. The bottle was light and made of plastic. By the end of the day, he hoped it would be heavy with coarse gold.

By the time he arrived at the spot where he had quit

Higher up on the bar he located a madrone tree, tossed a few stones out of the way, plopped down under its shade, and slumped back against its trunk to leisurely huff on a cigarette. From his resting place, he studied the creek for a likely spot to begin

He spotted a location upstream that looked promising. Drawing deeply on his smoke, he exhaled slowly. With closed eyes, he visualized his gold bottle crammed full of bright, yellow nuggets. His body tingled; a grin parted his lips.

CD’s creek

Let’s examine a couple of CD’s

Crevice Tool (Scratcher)

His crevice tool (scratcher) is a simple device about 18 inches long, constructed from 3/16” square metal that has been bent and twisted into a handle on one end and formed into a gooseneck, sharpened to a point, and tempered on the other—the business end. It is designed to scrape, loosen, and dislodge tightly packed gravel in bedrock crevices.

There are many excellent designs on the market today; however, snipers often fashion their own crevice tools at home or rob them from their toolboxes (screwdrivers for example). Although most snipers have a favorite crevice tool they use for most occasions, they often have several more for special applications.

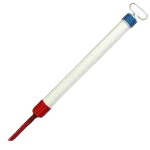

Suction Gun

His suction gun is used underwater to capture and temporarily store gold in its barrel. To function, the plunger arm is pulled back to suck in water and solids (ideally gold). It can also be pushed forward to force concentrated jets of water onto targets, such as cemented or tightly packed gravels in a crevice, to loosen and break them up.

Note: I used to build my suction guns from automotive grease guns. In my opinion, for underwater

sniping , they were superior to the hand held “dredges” and bulb suckers that are being sold to snipers nowadays.The “hand dredges” are too big and impractical for an underwater sniper to carry all day long with the rest of his

sniping tools; the bulb suckers are good; they’re small, easy to carry, are used by many snipers, and do a fair job of sucking up the gold in most conditions. But they don’t have the suction power or produce the blasting force of the modified grease gun that I prefer.

After resting and cooling off, CD climbed back into his gear, picked up his tools, and soon arrived at the spot on the creek that had caught his eye. Standing at the water’s edge, he assessed the site’s potential. His attention was focused on a spot just downstream from a five-foot waterfall where the stream had widened and the current had slowed.

His eyes were fixed on a run of slate bedrock in the creekbed that had, for the most part, been swept clean of gravel by fast water for 50 or 60 feet below the falls. A three-inch-wide, gravel-packed crevice suggested real possibilities. It ran perpendicular to the channel and snaked across the center of a wide, 2-foot-deep bowl-shaped depression in the bed of the stream.

At his feet, the crevice sloped down into the water and become concealed under a foot of gravel in the bowl. The crevice reemerged on the other side of the overburden and continued across the streambed where it pinched into a hairline crack on the opposite bank.

He stepped into the creek and knelt in the water on the downstream side of the gravel heap. Facing upstream, the water rushing and foaming past at chest level, he dropped his tools on the streambed beside him.

Me

Gad Bar

With hands protected from abrasion by rubber gloves, he pushed and pulled against the largest rock in the overburden, a rounded boulder, half-buried in the gravel. It weighed approximately 80 lbs, was stuck hard to the bottom layer of fine sediments, and wouldn’t budge. He forced his gad bar under the stubborn boulder and rocked it back and forth to break it loose.

Then with arms hugging the rock, he lifted it and strained to stand and toss it behind him. The boulder smashed like a cannonball against a raised knob of bedrock. With a resounding kerplunk, it bounced back into the creek on the downside of the bowl, spraying water in all directions. A hole was left behind in the overburden where it had been stuck. At least it was out his way.

Small Shovel Head

Back to kneeling in the creek, he removed half a dozen more heavy rocks, grabbed his shovelhead, and using both hands, scrapped into the remaining gravel, pulling toward him and away from the crevice.

Some of the lighter sands and pebbles lifted into the current and swept downstream in a swirling cloud, while the heavier gravels begin to pile up around his knees. Rapidly, he was able to uncover two feet of the crevice.

Grabbing his facemask, he spit into it (to prevent fogging), rinsed it in the stream, and strapped it over his eyes. With his snorkel plugged into his mouth, he ducked underwater to get a better look.

The crevice was tightly packed with sand and gravel mixed with a tangle of ancient square nails, lead, and miscellaneous bits of iron. Rust had coated the contents in the crevice, cementing them firmly together, signaling that the crevice had not been disturbed in recent times (a good sign). From experience, he knew that where heavy objects such as iron and lead, often remnants of the Gold Rush days, accumulate in gold-bearing streambeds, gold is often present.

Rock Hammer

Repeatedly, to loosen them, he smacked the cemented gravel in the crevice with the sharp point of his rock hammer. Then, with his crevice tool, he scraped them repeatedly until the constituents separated.

Next, with a cupped hand, he vigorously fanned the crevice, directing strong pulses of water down into it while watching intently. Sand, pebbles, square nails, and a lead mini-ball popped up in a cloud of bubbles, swirled in the current, and settled on the downstream side of the crevice.

Among the ejected contents clearly visible against the dark slate bedrock were seven shimmering yellow flakes and dozens of tiny grains of gold. He sucked them all into the barrel of his

Peering into the crack, on what appeared to be the bottom of the crevice, he saw a scattering of pebbles lying atop a thin layer of heavy black sand peppered with tiny grains of gold. Gently this time, he fanned the crevice and sucked up the gold that was ejected. Estimating the value of the gold recovered so far at $25, a jolt of adrenalin squirted into his bloodstream and quickened his pulse.

With amplified enthusiasmm, and as much down pressure as he could muster, he raked the jagged crevice bottom several more times with his scratcher, stirring up a milky cloud of silt.

After fanning one last time to expose the true bottom. Two nuggets, weighing between 1½ and 2 pennyweight each, and a couple of dozen flakes of gold, were revealed on an otherwise spotless bedrock bottom. (One pennyweight is equivalent to 1/20th of a troy ounce of gold.)

Always on guard, he darted his head above water and scanned up and down the creek looking for movement—bright colors—anything out of place, before recovering the gold. It’s a practice he repeats. unconsciously, multiple times daily, whether or not he is finding gold.

He cleaned out the crevice from end to end. Afterwards, he spotted a narrow vug-hole (cavity) on the bottom of the channel just upstream a few feet. A profusion of tiny teeth-like quartz crystals, caked in orange silt, lined its narrow walls. He was unable to see into the hole, or eject its contents with his scratcher. Inserting his

After the smoke cleared, six melon seed-sized nuggets and a one-half-ounce slug of gold appeared on the slick bedrock near the downstream edge of the vug.

He drew the smallest nuggets into his suction gun, but the half-ouncer was too large to pass through its tube; he took off his glove to pick up and admire it before dropping it into the bottle tucked away in his suit.

In total, he had spent 25 minutes working the crevice and vug hole, and he had recovered close to an ounce of gold. It had been a spectacular start to his day—and he still had the vug hole to finish and the rest of the day to snipe.

In Conclusion:

Sniping for gold can be defined in simple terms as the art of locating plausible gold catches, usually on or near bedrock and easy to access, removing the overburden, if any, recovering the gold, if any, and quickly moving on to the next juicy looking spot—if any.

Sniping is a poor man’s craft as opposed to serious, large-scale mining, which often involves huge capital investments and long-term risks that are far in excess of those associated with

However,

Techniques have evolved using (among others) gold pans, sluice boxes, highbankers, dredges, drywashers, metal detectors, and sometimes, heavy equipment.

Sniping is a hit-and-run, skim-the-cream-off-the-top sort of strategy that has been employed by gold hunters for centuries. In our own country, not all that long ago, hundreds of unemployed Depression-era men together with a smaller number of women (some with children) turned to the gold-bearing streams of California’s Mother Lode district to snipe for gold in order to survive those harsh, lean years. Most were only making from pennies to a dollar or two a day, but it was enough to get them through those tough times.

One man and wife team of snipers from those years was Jesse and Dorothy Coffey. Accompanied by their fiery little dog, they made a living

Throughout the Depression, they camped and sniped alongside creeks and rivers in California’s Mother Lode. And, thankfully, they bequeathed to us an exciting account of their four-year-long adventure in the form of a biography as told to and written by George Hoeper.

The work is titled, Bacon & Beans from a Gold Pan; it’s an entertaining, heartwarming, inspirational read, and I highly recommend it. In fact, I like it so much, I re-read it every few years—usually on a cold winter’s night, snuggled up to a warm, cracklin’ fire with a favorite beverage and bucket of popcorn at my side.

Unfortunately, the book is out of print as of this writing and used copies are becoming hard to find—but it’s worth the effort.

Check out Amazon's extensive selection of top-notch gold prospecting and mining tools and equipme...

As an Amazon affiliate, I earn a small commision, at no additional cost to you, whenever a qualifying purchase is made.